James O’Donnell, the merchant who banked on education for all: pioneering vision in nineteenth-century Ireland and Newfoundland.

By Yann Blake

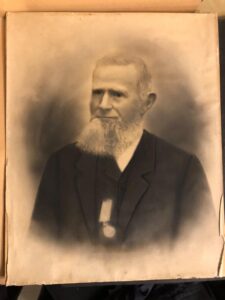

James O’Donnell was born around Cahir in County Tipperary, Ireland, around 1829, into a time of great economic and social change. As a young man, he left Ireland, emigrating to Newfoundland between 1843 and 1849. His journey was one of altruism, intrepidity and enterprise, culminating in an influential career in the spirits global trade alongside local wholesale and retail of groceries and fish merchandise – leading to an enduring legacy in both Newfoundland and Ireland.

O’Donnell’s decision to emigrate coincided with the devastating years of the Great Famine (1845–1852), a period during which many Irish sought refuge in North America for better opportunities. Newfoundland, with its strong Irish presence, was a natural destination, especially because several of James’ relatives were settled over there already. Upon arrival, He joined iniatives that supported Irish Immigrants (especially those struggling to make a living), and driven by his sense of generosity, he began sending home for financial aid to assist those in need. Maire Tierney, a relative, recalled:

“He was a brilliant businessman and had both gifted hands and a spirit of goodness and a desire to help all. He emigrated to Newfoundland as a young man. There he found many Irish immigrants struggling to make a living and sent home for some financial help to assist them and sent the less well-off back to Ireland.” [Family Testimonials]

Irish migration to Newfoundland commenced in the late seventeenth century and reached its height during the first two decades of the nineteenth century, a period during which an estimated 35,000 Irish individuals arrived on the island. Initially, the majority of these migrants travelled on a seasonal or temporary basis, primarily to engage in the transatlantic cod fishery. However, as the structure of the industry evolved from a migratory to a more permanent, resident-based model in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, a significant portion of the Irish population began to settle permanently in Newfoundland and Labrador.

As a young Irish settler, James O’Donnell, focused on the fishing trade during this transformative period. He is believed to have been among the first entrepreneurs to introduce the practice of preserving large quantities of fish in brine or pickle—a technique reminiscent of methods traditionally used in Ireland for curing ham. This innovative approach was key to helping his Irish family and friends by sending them food supply. A statement of Crown rents submitted during the Fourth Session of the Third General Assembly of Newfoundland in 1846, when O’Donnell was just 17 years old, lists him among the tenants of such properties

O’Donnell’s business activities extended beyond fisheries. Following the catastrophic fire of 1846 that devastated much of St. John’s, he acquired and repaired several damaged properties, which he then offered at the lowest rates, particularly favouring Irish workers.

O’Donnell’s business activities extended beyond fisheries. Following the catastrophic fire of 1846 that devastated much of St. John’s, he acquired and repaired several damaged properties, which he then offered at the lowest rates, particularly favouring Irish workers.

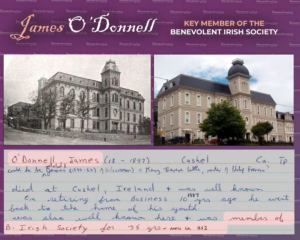

In 1852, James O’Donnell became a member of the Benevolent Irish Society (BIS), an organization founded in 1806 to aid impoverished Irish immigrants and promote their welfare in St. John’s. His philanthropic inclinations were evident from the outset: he not only participated in the society’s charitable initiatives but also became a key benefactor, funding the construction of essential facilities in the city.

The BIS, which by the 1840s had emerged as a formidable civic institution second only to the colonial government in influence, played a significant role in the social infrastructure of Newfoundland. In 1845, its president, Patrick Morris, declared that the Society’s finances were “flourishing beyond precedent.” That same year, the BIS trustees approved a loan of £1,734 to the colonial government for the construction of the Colonial Building, the future home of the legislature. The following year, in response to the potato blight that affected outport communities, the BIS distributed 76 barrels of seed potatoes to assist in the re-establishment of local agriculture.

Although officially non-sectarian throughout the nineteenth century, the BIS was widely recognized as a Roman Catholic men’s society. In 1876, while James O’Donnell had become an active member and key donator, the BIS facilitated the arrival of the Irish Christian Brothers in St. John’s and later supported the operation of St. Bonaventure’s College and the St. Patrick’s Hall School. Following the destruction of its clubrooms, St. Patrick’s Hall, in the Great Fire of 1892, the Society oversaw the rebuilding of the facility.

O’Donnell’s personal and philanthropic distinction was recognised in 1860, when he was presented with a gold pocket watch engraved with his name, crafted by John Donegan (1794–1862), one of Ireland’s most renowned nineteenth-century master jewellers and watchmakers. Based in Dame Street, Dublin, Donegan was celebrated for his craftsmanship and civic generosity: he produced religious paraphernalia for missionary priests and commemorative items for Irish patriots, including a silver crucifix for the coffin of Terence Bellew MacManus, a leader of the Young Ireland movement. Donegan also donated generously to institutions such as All Hallows College in Drumcondra and the Armagh Cathedral, for which he created numerous sacred vessels embellished with diamonds. This early recognition and O’Donnell’s continuous civic engagement foreshadowed the legacy he would later consolidate both in Newfoundland and, eventually, upon his return to Ireland.

Success in the Fishing Industry and International Trade of Spirits

O’Donnell’s business acumen led him into the fishing industry, where he pioneered new methods of fish preservation. He is believed to have been one of the first to experiment with large-scale brining of fish, similar to the techniques used for preserving ham in Ireland. His enterprise flourished, allowing him to reinvest in the Irish community in Newfoundland. He purchased and repaired houses, offering them at affordable rates to his workers, creating stable homes for many newly arrived Irish immigrants.

In addition to his success in the fish trade, O’Donnell expanded his business interests into the liquor trade. According to Ye Olde St. John’s (1750-1936), O’Donnell was a well-known figure in the commercial scene of St. John’s, operating a wholesale and retail trade in wines and spirits. His business was located at 290 Water Street, as noted in Newfoundland business directories from 1864 to 1886. He was described as a “popular man of his day,” possessing “a rare fund of wit and humor and a good word for all the world” (Ye Olde St. John’s, p. 52).

In addition to his success in the fish trade, O’Donnell expanded his business interests into the liquor trade. According to Ye Olde St. John’s (1750-1936), O’Donnell was a well-known figure in the commercial scene of St. John’s, operating a wholesale and retail trade in wines and spirits. His business was located at 290 Water Street, as noted in Newfoundland business directories from 1864 to 1886. He was described as a “popular man of his day,” possessing “a rare fund of wit and humor and a good word for all the world” (Ye Olde St. John’s, p. 52).

The O’Donnell store at 290-288 Water Street still stands in St Johns, Newfoundland. The buildings at 288-290 Water Street, which remain standing today, were reconstructed after the devastating fire of 1846, marking them such significant historical structures in St. John’s, Newfoundland. Sometime before the 1860s, James O’Donnell took over the building at 290 Water Street and established a wholesale and retail business that dealt in liquors, spirits, preserved fish products, and general groceries, becoming a prominent merchant in the area.

By 1886, O’Donnell sold his business, including stocks and trade, to J.J. O’Reilly but retained ownership of the building, along with other properties in Newfoundland (Belvedere). The rental income from these properties funded several scholarships in schools in Ireland, following O’Donnell’s commitment to education and philanthropy values. After returning to Ireland in 1887, O’Donnell continued to receive rent from his Newfoundland properties, ensuring a steady income stream for his scholarships – especially the education of his extended family. The historical significance of the 290-288 Water Street building was further strengthened when it survived the Great Fire of 1892 in St. John’s, making it one of the few structures to withstand the blaze. Post-1900, the income from these properties continued to support scholarships, such as one at Rockwell College which was receiving the rents funds via James M. Kent, a prominent lawyer, even after O’Donnell’s death. The properties were eventually sold. 290-288 Water street was divided and new businesses took over, continuing the life of this historic site.

“Next door came the store of James O’Donnell, a bachelor, from the Old Country, and a very popular man of his day. He had a rare fund of wit and humor and a good word for all the world. Possessing all these genial and attractive qualities his friends always wondered that he remained a bachelor. He went back to Ireland in his old days and it is said spent his declining years in a monastery. Like Strickland and Rankin he carried on a wholesale and retail trade in wines and spirits. Amongst the clerks ,was James Crowdell and the well known Maurice Corcoran, alias “Kidney Feet.” The O’Donnells were a prominent family in Newfoundland in the sixties and seventies. Revds. Jeremiah, David and Patrick were priests, and there was a sister a Nun. The other sister married Mr. Leamy, a prosperous Irish farmer of the Blackhead Road. It was Father O’Donnell who was wounded by a gunshot at the time of the ’61 election riots. He came to Market House Hill to plead to the rioters to disperse. Mr. John O’Donnell, the pipe-fitter mild heating installer, of this city, is a descendant of this family, his father being the late Thos. O’Donnell, J.P., ore-time Magistrate at Placentia and Bell Island. Mr. C. E. A. Jeffrey, Editor of the Evening Telegram, is also in direct descent from the family on his mother’s side, his father, Rev. Mr. Jeffrey, having married a daughter of an O’Donnell of the above family. The late Mr. J. J. O’Reilly succeeded Mr. J. O’Donnell and carried on the liquor business wholesale and retail till his death.” [Book: Ye Olde St Johns]

A Lifelong Commitment to Ireland and Family

Despite his success in Newfoundland, O’Donnell remained deeply connected to his homeland. He frequently sent barrels of salted fish back to Ireland to assist his family and neighbors. One of his contemporaries, Ned Kelly, the son of Ellen Kelly (née O’Donnell) – herself great-niece of James O’Donnell described the excitement these shipments brought:

“James often sent home barrels of salted fish to members of his family and his old neighbors too. Ned Kelly recalls barrels of salted fish arriving into the port of Waterford and family and friends going to pick up their deliveries, it was like Santa Claus coming to the folks at home.” [Family Testimonials]

James O’Donnell frequently spent time with his cousins Rev. Jeremiah O’Donnell and Rev. Richard O’Donnell while in Newfoundland. He even is mentioned as travelling from Newfoundland to Liverpool in July 1879 with both of them.

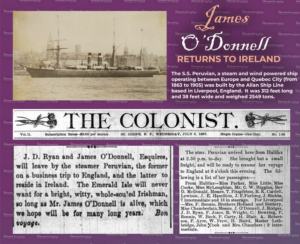

O’Donnell regularly returned to Ireland for holidays, spending time in his community and using his skills to help repair homes and buildings. For example, in August 1882, he is mentioned in the newspapers as visiting Dublin and staying in the European Hotel. However, as he aged, he decided to retire permanently to Ireland around 1887.

O’Donnell regularly returned to Ireland for holidays, spending time in his community and using his skills to help repair homes and buildings. For example, in August 1882, he is mentioned in the newspapers as visiting Dublin and staying in the European Hotel. However, as he aged, he decided to retire permanently to Ireland around 1887.

“Dear Sir – Enclosed find Union Bank bill of exchange, London for £12 16s 8d sterling, which sum place to the credit of the Ladies’ Land League or P.P.S. Fund, whichever need it most. Please insert the enclosed names of subscribers in your truly patriotic journal, and oblige yours truly, James O’Donnell, P.S. We have no L. League in this country. – J. O’D.” [Newspaper The Nation, 11 March 1882]

Philanthropy and the Salvation of Rockwell College

“J. D. Ryan and James O’Donnell, Esquires, will leave by the steamer Peruvian, the former on a business trip to England, and the latter to reside in Ireland. The Emerald Isle will never want for a bright, witty, whole-souled Irishman, so long as Mr. James O’Donnell is alive, which we hope will be for many long years. Bon Voyage.” [Newspaper The Colonist, 6 July 1887]

Upon his return, O’Donnell’s health began to decline, but his philanthropic spirit remained strong. Around this time, Rockwell College, a prominent institution in Cashel, County Tipperary, faced financial difficulties and was at risk of being purchased by a French religious order. In an extraordinary act of generosity, O’Donnell donated his entire fortune, as well as the annual income from his properties in Newfoundland, to the Holy Ghost Fathers at Rockwell College. This act of beneficence enabled the Holy Ghost Fathers to establish their first foundation at Rockwell in 1896.

” To the Editor of The Nation. Rockwell, Cashel, Co. Tipperary, Nov. 30th, 1896. Dear Sir – Enclosed find National Bank Note for £1 to help the good cause you advocate in your truly honest paper, hoping soon to see the Fund not many thousands for Ireland. I am, yours, James O’Donnell” [Newspaper The Nation, 5 December 1896]

The Derry Journal (30 December 1896) and The Nation (5 December 1896) both reported indirectly O’Donnell’s contributions to Rockwell College. Archbishop Croke laid the foundation stone for the new buildings in June 1896, marking a new era for the college.

Final Years and Enduring Legacy

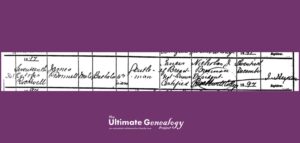

In the final days of his life, O’Donnell was received into the Holy Ghost Fathers, fulfilling a spiritual calling that had guided his charitable works. On October 17, 1897, at the age of 68, James O’Donnell passed away at Rockwell College in Cashel, County Tipperary, Ireland. At the time of his death, he was residing with the Holy Ghost Fathers, also known as the Spiritans. The cause of death was certified as breast cancer, a condition that, while rare in men, was recognized and diagnosed even in the 19th century

O’Donnell’s death was recorded in Newfoundland, noting his passing as a significant event in history books. His civil death record referred to him as a “Gentleman,” reflecting his standing in the community. His last will and testament included a generous donation of £200 directly to Rockwell College, equivalent to approximately £22,100 in 2025. Additionally, he established a bursary with funds ranging from £100 to £200 per year to support educational initiatives.

Following his death, O’Donnell’s will specified that £150 be given to the Ladies’ Society of Saint-Vincent de Paul. In today’s terms, this amount would be worth approximately £11,725.83, highlighting the significant value of his bequest. In 1900, £150 could purchase substantial assets such as five horses, 15 cows, 277 stones of wool, or 117 quarters of wheat, and was equivalent to the wages of a skilled tradesman for 454 days.

James O’Donnell was laid to rest in the graveyard of Rockwell College, where a headstone marks his grave to this day. The graveyard was typically reserved for priests or those ordained, making James O’Donnell one of the few – if not only one – buried there, who wasn’t an ecclesiast. His burial at Rockwell reflects his unique status and the respect he commanded within the community. O’Donnell’s legacy continues to resonate through his philanthropic contributions and the enduring impact of his generosity on the institutions and individuals he supported, and the many generations that followed.

For years after his death, a special educational fund, financed by the income from his Newfoundland properties, supported the education of his relatives. However, as Maire Tierney noted, the properties were eventually sold, and the fund ceased to exist:

For years after his death, a special educational fund, financed by the income from his Newfoundland properties, supported the education of his relatives. However, as Maire Tierney noted, the properties were eventually sold, and the fund ceased to exist:

“For years after his death, there was an education purse for members of his family. The money came from the annual income from the property in Newfoundland, but unfortunately, the property has been sold, and the purse is no more. But, for a long time after 1897, many educations were covered by this man’s generosity.” [Family Testimonials]

O’Donnell’s story is not just one of business success but of an enduring commitment to the welfare of others. From assisting struggling Irish immigrants in Newfoundland to securing the future of an educational institution in Ireland, his legacy is one of selflessness and service.

Watch a short video on James O’Donnell here

References

- [Book] Ye Olde St. John’s, 1750-1936.

- Derry Journal, December 30, 1896; January 4, 1897.

- The Nation, December 5, 1896.

- Newfoundland Will Books, Vol. 6, pp. 442-444 (Probate year 1898).

- Mannion Collection, Card (Ref. e100005621).

- Rochfort’s Business Directory of Newfoundland, 1877.

- Newfoundland 1864-1865, 1880-1881, 1885-1886 Directories.

- Freeman’s Journal, August 15, 1882.

- The Diary Of The Rev O’Driscoll (1874-1881)

- [Book] Notable events in the history of Newfoundland: six thousand dates of historical and social happenings, 1900.

List of Newspaper Articles

Derry Journal

- December 30, 1896 – Page 5

- January 4, 1897 – Pages 6-7

The Nation

- December 5, 1896 – Pages 11 + 3

- March 4, 1882

- March 11, 1882 – Page 13

- December 6, 1884

Freeman’s Journal

- August 15, 1882 – Page 5

- November 28, 1884

Evening Telegram

- July 10, 1879

- September 6, 1881

- October 28, 1881

- December 14, 1883

- March 4, 1886

- July 6, 1887

Evening Mercury

- May 6, 1882

- October 8, 1883

Temperance Journal

- March 13, 1885

Times and General Commercial Gazette

- November 23, 1870

North Star and St. John’s, Newfoundland News

- December 11, 1875 – (Unclaimed Letters: James O’Donnell)

Terra Nova Advocate

- April 18, 1877

Colonist

- March 10, 1886

- March 18, 1886

- April 10, 1886